Bridging the gap 33.23

In case you missed it ...

Not a subscriber yet? Click here

('Bridging the gap' is free)

Here is a selection of recently published Deep Dives, Perspectives and Quick Insights that our subscribers get to read in full.

- Minimising cost overruns - part 2 (Built Environment / Wellness)

- Retrofitting away operational and embodied carbon (Built Environment / Wellness)

Plus a few from the archives:

- Electric trucks - the future of freight? (Greener Energy Applications)

- Artisanal mining - seeking solutions (Transitions / Human Rights, Agriculture / Natural Capital)

- Will half the world starve without fossil fuels? (Agriculture / Natural Capital)

What subscribers are reading this week

Minimising cost overruns - part 2

(Built Environment / Wellness, Premium and Professional)

Master architect Frank Gehry consistently defies the odds, producing projects of staggering beauty while meeting time and budget targets.

A study of 16,000 major projects—from large buildings to bridges, dams, power stations, rockets, railroads, information technology systems, and even the Olympic Games—reveals a massive project-management problem. Only 8.5% of those projects were delivered on time and on budget, while a mere 0.5% were completed on time and on budget and produced the expected benefits. In other words, 99.5% of large projects failed to deliver as promised. Simple and modular projects did best.

This has massive implications for the sustainability transitions. A recent report from McKinsey for instance, estimates that "spending on physical assets that could help reach net zero would need to rise from $3.5 trillion spent per year today to $9.2 trillion annually. Total spending through 2050 could reach $275 trillion".

However, there is a small subset of complex projects that did deliver. These are the buildings designed and constructed by the architect Frank Gehry. You will know at least one of these, the Guggenheim Museum in Bilbao. It was not only delivered on time, but the cost actually came in under budget, and it generated benefits well above those expected. Bent Flyvbjerg and Dan Gardner argue there is much we can learn from Gehry.

Given how much is at stake, both financially and from a sustainability perspective, these are lessons we need to learn, and fast.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Retrofitting away operational and embodied carbon

(Built Environment / Wellness, Professional)

In August of 2022, Supertech's residential twin towers in Noida, Uttar Pradesh were demolished, almost thirteen years after construction work started. The Supreme Court had ruled that the towers were constructed in violation of the UP Apartments Act 2010. Supertech believed that they had full approval in 2019 “strictly in accordance with the then prevailing byelaws.”

It was the first time that a building taller than thirty floors had been demolished.

A similar demolition in the municipality of Maradu in Kerala two years previously offered clues to potential issues. One resident claimed that cracks had appeared in the roof of his house as a result of the controlled implosion that demolished the Alfa Serene twin apartment block, while another said his neighbour died from Covid-19 complications while waiting for INR4m ($60,000) compensation. Dust from the rubble that needs to be cleared from the site, to make way for the next construction can linger in the air causing pollution and exacerbating conditions such as asthma. The Central Building Research Institute had installed black boxes in the towers to obtain data to help design future demolitions.

But looking more broadly, when buildings come to the end of their useful life should they be demolished at all?

There are a number of ways in which existing structures can be repurposed when they reach the end of their useful operational life. Indeed even while they are operational, their overall efficiency can be improved to improve their sustainability. This can involve retrofitting more modern, low carbon, energy efficient technologies and features or even reusing materials and elements from existing structures that have themselves come to the end of their lives. There are a number of examples including Kristian Augusts Gate 13 in Oslo, Good Cycle Building 001 in Nagoya and Battersea Power Station in London (pictured).

There are strong financial arguments in terms of longer term value creation. The funding structures need to suit the development. For residential properties including community-based infrastructure, rather than an individual approach, a 'place-based' approach may be more appropriate.

Link to blog 👇🏾

From the archives

Electric trucks - the future of freight?

(Greener Energy Applications, Premium and Professional)

While it might appear from recent news stories that the debate about what will power the trucks/HGV’s of the future is ongoing, in reality it's actually pretty much already decided. Short of any surprises in the next couple of years, it's going to be electricity. There is still an ongoing discussion about battery charging vs overhead power, but the notion that we will be using hydrogen or biofuels at any scale is fading, and fading fast. But the process has really only just started, and we have some tough decisions ahead of us.

Decarbonising transport, especially heavy transport, is partly about GHG emissions, but it's also about reducing air pollution - while at the same sustaining the freight transport sector. At present pretty much everything we consume spends at least some time in a (currently) diesel truck/HGV. Our freight infrastructure is essential to our economy. We need to be realistic. This is not going to be an easy or low cost transition. Issues include what charging infrastructure do we need, the capacity of our electricity grid, who pays for any overhead power lines, and of course financial support for early adopters.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Artisanal mining - seeking solutions

(Transitions / Human Rights, Agriculture / Natural Capital, Professional)

The increasing focus on supply chains for the critical minerals used in green technologies has also brought the topic of artisanal mining to the fore. It remains a controversial and not well understood topic. It's frequently portrayed in a negative way, with governments often describing it as "illegal mining", calling for it to be banned. It's not that simple. Most miners lack choice. As with other transitions there are solutions, but perhaps not the obvious ones.

One of the big challenges in decarbonising our society relates to the supply of critical raw materials. This is not just about cost, it also covers where they are sourced from, how they are produced, and how can we manage and mitigate the inevitable negative impacts. Intrinsically tied up in this is the issue of mining. For many minerals we are going to need more mining (and mineral processing), not less. Which means we need to think deeply about what mining means for local communities, and how we can make mining more environmentally and socially sustainable.

This is the first in a series of blogs on artisanal and small-scale mining from Rob Karpati, of the Blended Capital Group. Rob is passionate about mining, especially finding practical solutions to artisanal mining. The team he works with believe that opportunities for extreme impact exist, requiring the development of an investment marketplace as well as a focus in rights in order to mitigate structural challenges.

Link to blog 👇🏾

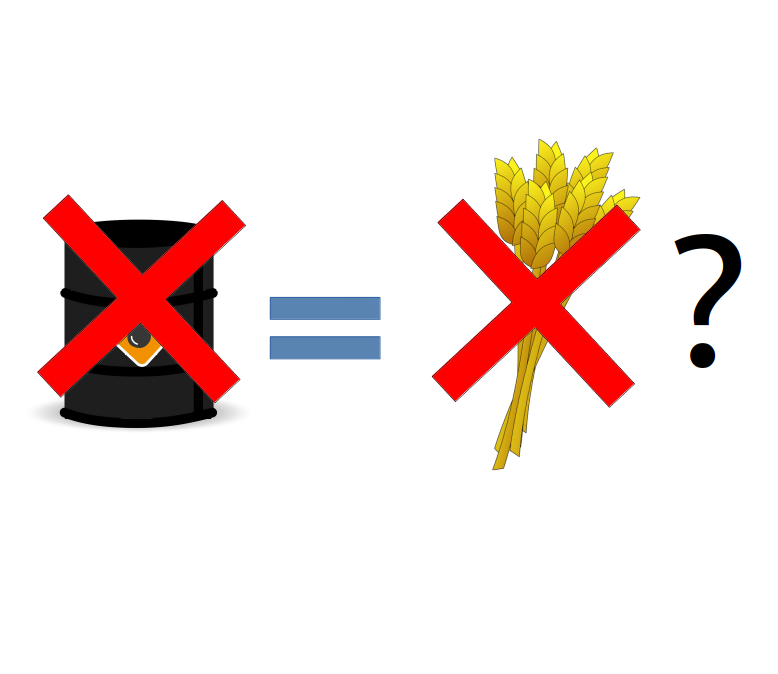

Will half the world starve without fossil fuels?

(Agriculture / Natural Capital, Professional)

Our World in Data is a fabulous source of data, charts and insights. Back in April, one such chart - 'World population supported without synthetic fertiliser' and 'World population fed by synthetic fertiliser' - with an excellent accompanying article from the brilliant Hannah Ritchie, has been used by a number of commentators to make the assertion that 'stopping oil and gas production means half the world will starve.'

This intrigued us, so we thought we would explore.

There are actually a number of separate questions within that assertion:

(1) Do we need oil and gas (hydrocarbons) to make synthetic fertilisers? The answer to this is currently (mostly) yes, but low carbon alternatives are emerging fast.

(2) Do we need to use so much synthetic fertilisers? The answer to this is no - we’re incredibly inefficient in our use of fertilisers in some areas, and we’re using far more than we need.

(3) How do we feed the World population? (how much food do we need?) To answer this we need to think about the entire food system, not just farm production. We can do much more with less inputs.

Link to blog 👇🏾

Please forward

to a friend, colleague or client

If this was forwarded to you, click the button below and sign up for free to get 'Bridging the gap', 'What caught our eye' and the 'Sunday Brunch' in your inbox every week.

Please read: important legal stuff.