Biodiversity - the financial case

It might seem that reversing the impacts of biodiversity loss is a government problem, but solutions at the company and financial investor level are emerging, but they need nurturing and developing.

Summary: It might seem that reversing the impacts of biodiversity loss is a government problem, but solutions at the company and financial investor level are emerging, but they need nurturing and developing. As part of this, as well as our regular work on Human Rights, this year we have started to draw in adjacent issues, in particular Biodiversity. To us this is going to be one of the key “emerging” risks for investors, asset managers and companies over the next few years.

Why this is important: As the concept of double materiality gains more traction, companies, investors and asset managers need to be more informed about the legal and financial risks related to the impact that their activities have on the wider world. Fully half of the world’s total economic activity – around A$61 trillion – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services.

The big theme: Human rights are a big theme in their own right. What is sometimes less appreciated is that they are intrinsically linked to a series of wider social and environmental topics. One of these is the importance of bio diversity, which is both an environmental and a societal/human challenge. Companies and investors need to stay ahead of the curve on this. These are not just good corporate citizen topics anymore; they are becoming a critical driver for a company's long term financial success or failure.

The details

Summary of a story from The Conversation

As the economist Herman Daly pithily said, the economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment – not the reverse. Nature makes our lives possible through what scientists call ecosystem services. Think healthy food, clean water, feed for livestock, building materials, medicine, flood and storm control, recreation, and attractions for tourists. Despite this, Australian businesses and financial institutions have so far failed to track how their activities both rely on and affect nature. This means our investments and superannuation could be exposed to hidden financial risks because of nature loss – and may also contribute to the destruction of nature.

That’s set to change. The private sector is waking up to nature’s value (and the risks of losing it). The world’s biodiversity rescue plan agreed to last year could help motivate governments and businesses to clean up their investments by directing more money to protect nature. There’s one crucial plank we’re missing though – mandatory reporting of how businesses both depend on and impact nature.

Let's look at why this is important...

Why this is important

Fully half of the world’s total economic activity – around A$61 trillion – is moderately or highly dependent on nature and its services. Nature and Biodiversity matter, and yet so far they have not got the attention they deserves.

Our expectation, as non legal specialists, is that biodiversity will partly follow the path first established by human rights - one of increasing regulation. We explained some of this in an earlier blog we wrote in January, that was built around the recent Commonwealth Climate and Law Initiative (CCLI) blog, that asked “can you price pollination ?”.

As we highlighted in that blog, the recognition of climate change as being a material financial risk led to investors being required to integrate such risks into their analysis, or risk breaching their fiduciary duties. In some cases, investors may be required to go further, and look to mitigate these risks via their investments.

As biodiversity loss is becoming increasingly recognised in the same way, investors should expect their legal obligations to also expand. Where financial institutions fail to consider biodiversity, they may expose themselves to the risk of litigation. For example, in Australia, a potential claim has been indicated against ANZ Bank on the grounds that its directors’ report does not disclose the financial materiality of biodiversity loss and describe how exposure to biodiversity risk is managed, as required by Australia’s Corporations Act.

In Europe, the German Supply Chain Due Diligence Act, which we wrote about back in Nov 2021, is placing more responsibility on companies to ensure that they carry out better due diligence on their supply chains. And the proposed EU law on deforestation free supply chains, which we touched on in yesterday's blog on palm oil, further adds to the pressure.

For today we want to start exploring a slightly different topic, the financial case for biodiversity.

Obvious investible opportunities exist around water and wastewater testing and treatment, but these are relatively small sectors. The really big opportunity for investors to positively contribute is via agriculture and our food. This is a broad topic, for instance we recently wrote on household food waste, with Australian’s wasting c. 102kg per person per year (you don't need to grow what you don't waste). But for this blog, we want to focus on farming practices.

Anyone who has followed the biodiversity topic for a while will be aware of the Dasgupta Review, carried out for the UK Government. In it he sets out the problem …collectively we have failed to manage our global portfolio of assets sustainably. Estimates show that between 1992 and 2014, produced capital per person doubled, and human capital per person increased by about 13% globally; but the stock of natural capital per person declined by nearly 40%. Estimates of our total impact on Nature suggest that we would require 1.6 Earths to maintain the world’s current living standards.

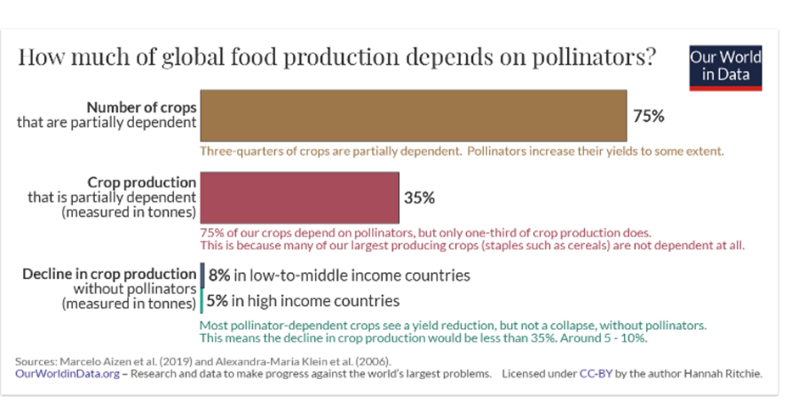

The report specifically calls out agriculture - food production is seen as the most significant driver of terrestrial biodiversity loss. And it's arguably the sector in which investors and companies can make the most difference. One aspect of biodiversity that has a material impact on agriculture is pollination. According to Our World in Data, c. 75% of our crops (by number) rely on pollinators, with around 35% of our crops (by tonnes) being pollination dependent.

But what can we do ? A common response is that this is a societal issue, on our own what can providers of capital do ? Remember, this is not just a case of “having more bees etc”. Pollinators rely on complex ecosystems, if one part breaks down the whole system is at risk of failure (you may remember the surge in bee colony collapse in the mid 2000’s).

Some solutions are starting to become more mainstream. One is highlighted in a recent blog from the Rotterdam School of Management (RSM), which looked at real world examples of projects and financial initiatives that focused on the key areas (regenerating top soil, increasing biodiversity, improving the water cycle, enhancing ecosystem services, supporting biosequestration, increasing resilience to climate change, and strengthening the health and vitality of farm soil). So, the wider farming ecosystem, sometimes called regenerative agriculture, although as with many ESG related terms, it's a term that is sometimes over used.

In the more detailed report that preceded the blog, they highlighted a number of ways that investors, both debt and equity, can assist with this process. First, provide access to finance for nature inclusive farms. Here loans should incentivise sustainable rather than intensive agricultural practices. This requires for a new framework for the perception of both risk and opportunity when it comes to agriculture. It also asks for a vision on transition pathways. Many farms that are currently employing intensive methods, lack the conversion capital to make the transition to nature-inclusive farming. This funding could come from traditional financial sources, but there also looks to be a role for new sources of capital, potentially seeking lower rates of return in exchange for wider societal benefits.

Second, use patient capital for farmland. Given the low-risk low-return character of agricultural land, organisations with patient capital, like pension funds, governments, and foundations, might be particularly well-suited to play an important role in the transition.

And third, mobilise private and public finance to convert intensive farmland to nature-inclusive farmland. The agricultural transition calls for greater collaboration between public and private sectors to scale the financing opportunities for sustainable agriculture. There is a precedent for this - the Dutch government has a big fund available to buy out farmers to tackle the nitrogen crisis. But it needs to be expanded and scaled up.

The RSM report highlights a number of ways that the financial sector can assist in the biodiversity transition. There are others - in future blogs we will explore Natural Capital Bonds, and the more controversial topic of carbon sequestration payments.

Something a little more bespoke?

Get in touch if there is a particular topic you would like us to write on. Just for you.

Contact us

Please read: important legal stuff.